The Scream Is Part of Which Style in Art

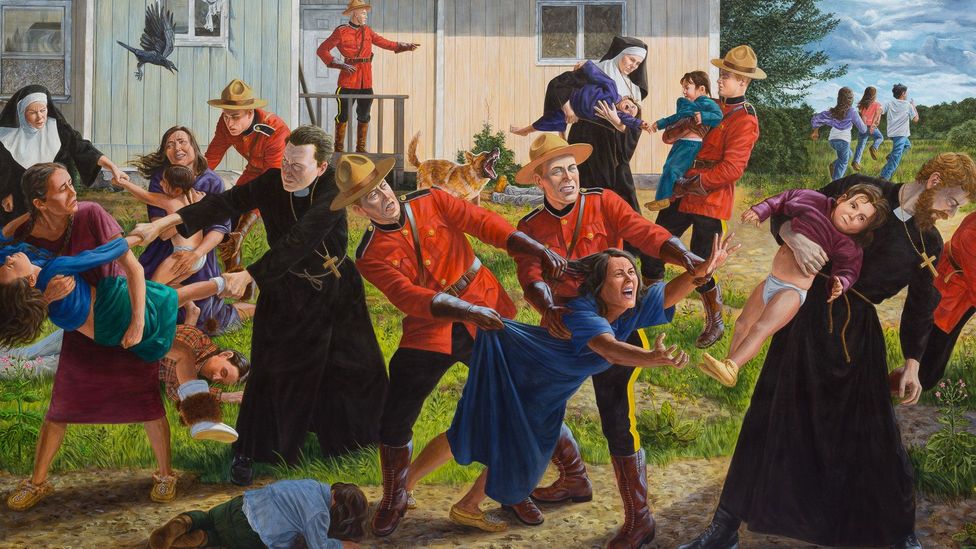

Kent Monkman's The Scream: Images that define atrocities

(Prototype credit:

Kent Monkman/ Collection of the Denver Art Museum

)

Some paintings accept become the defining images of a social or political ending. But can fine art actually shape the narrative of war and atrocity, asks Karen Burshtein.

Painted in 2017, The Scream has come to symbolise outrage and grief after the discovery of unmarked graves (Credit: Kent Monkman/ Collection of the Denver Art Museum)

Since the first discovery in May, Monkman's painting has been shared widely, in posts reflecting the country'south collective rage, grief and a sense of urgency. Thanks to social media, and the Covid-era practice of museums putting their collections online, images have never been more accessible to the public, to the point where they're frequently becoming symbols for the phonation of moral outrage confronting atrocity.

It was while looking at Old World paintings at Madrid'due south Museo Prado about a decade agone that Monkman, one of Canada'south nigh esteemed contemporary painters, began to see their emotional power. The creative person purposely appropriated Western artistic traditions of history paintings (and bright colours) to tell the story of The Scream: this is a shared history, he seemed to be maxim. (The painting was dedicated to Monkman's grandmother, who was a survivor of the Residential Schoolhouse arrangement; the offset time she spoke almost her feel at the school was on her deathbed.)

Putting it in context

This data about the painting, like then much else, including context, and scale (the painting is a huge 2 metres by 3 metres) is likely to get lost when it'southward viewed on Facebook. "They were showing this image all over the net and a lot of these places they weren't even maxim it was made by Kent Monkman," says MaryLou Driedger, a Winnipeg author and teacher, who worked every bit a bout guide at Winnipeg Art Gallery when the painting was on brandish as part of a cross-Canada Monkman exhibition, Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience. She tells BBC Culture: "If y'all don't know that this painting was fabricated by a Cree artist who spent the beginning five years of his life on a reservation, you are losing a lot of the story. Information technology'southward important to know that. And that he listened to every single 1 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission'due south testimonies before he did the paintings and I think to just blast this film over the net you lot're not getting much context."

Much about The Scream – including its calibration – is lost when it'due south viewed on social media (Credit: Kent Monkman/ Collection of the Denver Art Museum)

But The Scream is just 1 example of how, throughout history, artists' works have been used as tools of change. In some cases, the artists have made themselves proactive participants to issue social activeness and modify, even hoping to drive policy decisions. Their work of art becomes a calculated creation, the creative person abandoning apologue for activism. The artist hopes for a visceral impact so that the painting might raise an awareness of an injustice.

Merely how exercise artworks serve to interrogate an atrocity or an act of war? What happens when a painting goes from prototype to concept? And when the artist is asking the viewer non to be just the audience, merely a messenger, to carry their outrage to the greater world, what does that practice to the traditional relationship between artist and viewer? A more equal, or at least collaborative, human relationship – partners in advocacy – has been suggested, one that reflects people's power when associated with an artist.

"Since photography is seen as reality, images of violence are off-putting for an audience," Cameron Deuel wrote in The Human relationship Betwixt Viewer and Art, a 2013 newspaper for Western Washington University. Art can exist helpful by opening avenues that photography, or a text, can't. As Bracha Fifty Ettinger, a visual artist, philosopher, psychoanalyst and author, said in a 2016 word in The New York Times: "Art works toward an upstanding infinite where we are allowed to encounter traces of the pain of others through forms that inspire in our middle's heed, feeling and noesis. It adds an ethical quality to the act of witnessing. By trusting the painting as truthful y'all go a witness to the effects of events that you lot didn't feel directly, you get aware of the effects of the violence washed to others, now and in history – a witness to an event in which yous didn't participate, and a proximity to those you take never met."

And despite the limitations of social media, at that place is often greater touch when a work is seen outside of its most traditional habitation, the gallery or museum. It takes the perceived or actual elitism out of art, further empowering the viewer. A research project by the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid explores the impact of what one of its contributors, art dealer Tony Shafrazi, called "the greatest state of war painting in the world": Pablo Picasso's Guernica. The project, Rethinking Guernica, contains more than than 2,000 documents, essays and interviews. Fiddling wonder that the way in which art can serve to tell an atrocity is called The Guernica Effect.

Picasso'south Guernica helped garner support for the crusade against Franco's Fascism (Credit: Alamy)

In 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, Franco invited the Nazi Condor Legion to drop bombs over a small town, Gernika, that was a symbol of Basque independence. In Picasso'south jarring iconic oil-on-sail painting of the aftermath, civilians scream in anguish; scattered limbs are strewn throughout. Violence and hurting scream from the canvas.

While art critics scrambled to unravel the meaning of each figure represented in the piece, information technology could be argued that was beside the signal. As Picasso wanted, this painting went beyond standard art-analysis dialogue of aesthetic, technique and style. Though it was rendered in the Cubist style, as Shafri said, "It's beyond Cubism." Picasso chosen Guernica the "property of the people".

The artist, who painted the piece of work in the immediate backwash of the result to capitalise on news reports, sought to utilize the painting to influence changes in national policy, to galvanise earth opinion, and to push viewers into being proactive participants in the outrage. Picasso toured Guernica in the U.k. and US, as a fundraising endeavor for Spanish Relief for Guernica in 1938. While still in exile in French republic, Picasso even used the painting every bit a bargaining chip for democracy. In later years, Franco's followers wanted the painting in Kingdom of spain (perhaps owing to its glory), simply Picasso decreed he would merely allow it to hang in the land once democracy had been established.

The art of war

This idea of how well-timed art can shape the social narrative of war was explored by Nicole Dean, a Usa Army officer specialising in looted art. In a 2020 article, Dean proposed that Guernica could be used every bit a tool for leadership development: "This calculated cosmos of a powerful masterpiece should exist examined and appreciated as part of a greater wartime narrative."

She even suggested that art could exist used equally a guide to the art of war. "The study of wartime art tin be a valuable improver to the professional development of armed forces leaders, generating options for professional dialogue about how societies see the victors, the vanquished, and the value of conflicts through the lens of artists and cultural patrimony."

Earlier him, Picasso's fellow Spanish master artist, Francisco Goya, was a graphic bystander to the atrocities of his day – and his painting The Third of May 1808 (part of a diptyque with the Second of May, held by the Museo Prado in Madrid) continues to daze almost 2 centuries after his expiry, equally a ground-breaking masterpiece of art – and a political tool.

Goya's The Tertiary of May 1808 created a timeless image of violence from specific events (Credit: Alamy)

The painter was deeply affected past the disillusionment he saw during the Napoleonic invasion of Spain in May 1808, by widespread starvation among civilians and by their resistance – it was the first time the term "guerrilla warfare" was used – as well equally their subsequent execution at the hands of Napoleon'south troops. But it was the fashion Goya approached the painting that suggested the painter was focusing on a universal and timeless bulletin. The troops, guns pointed directly at the masses, are faceless. Many of the civilians embrace their faces. They could belong to whatever state, and any fourth dimension. (The anonymity was radically avant garde, rejecting all the usual conventions of Baroque and Neoclassical history painting for its 24-hour interval).

And it did indeed transcend time and place. In the words of art critic Robert Hughes, author of a 2003 biography of Goya, The Third of May 1808 is "truly modern… the motion-picture show against which all future paintings of tragic violence would have to measure out themselves… He speaks to us with an urgency that no creative person of our fourth dimension can muster. We run across his long-dead face pressed against the glass of our terrible century, Goya looking in at a fourth dimension worse than his." Later, Edouard Manet echoed The Third of May in tone and composition with his The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1868-69).

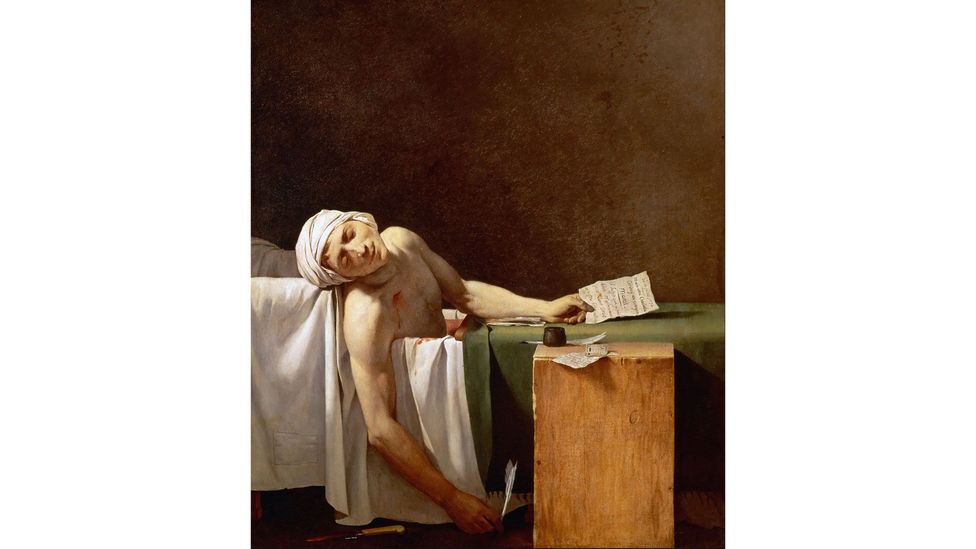

A 'propaganda painting', Decease of Marat was widely shared in its fourth dimension – and has become a meme today (Credit: Alamy)

Jacques-Louis David'southward Death of Marat (1793) might have been the first painting to shift public opinion in existent time, or as close to existent time as that day allowed. The painting depicts the murder of revolutionary leader and journalist Jean-Paul Marat who was stabbed in his bathtub. David one of the nigh prominent painters of his mean solar day, completed the work just several months afterward Marat's murder. Espousing academic techniques of the 24-hour interval, it's about photographic in its simplicity. Art historian TJ Clark called information technology the outset modernist painting, for "the style information technology took the stuff of politics as its cloth, and did non transmute it". This was calculated. David was an official creative person of the Jacobins, and was asked to make Marat into a martyr to the crusade. Marat was i of three "propaganda paintings" David painted.

Significantly, it was also turned into an engraving that was widely circulated amid the public. (Its popularity merely waned during the reign of terror merely returned to glory by the 1820s with the help of a flattering essay on it by Baudelaire: "This painting is David's masterpiece and i of the great curiosities of modernistic fine art because, by a strange feat, it has nothing trivial or vile…"). Today, the painting is ofttimes used as a meme in response to gimmicky conflicts, with a pepper-spraying policeman, for case, standing over the murdered field of study in the bathroom.

German artist Käthe Kollwitz wanted her 1923 painting War (Krieg) to be seen through prints that were distributed, or shared, like pamphlets. The artist sought a suitable response to the "unspeakably difficult years" of Earth War One that saw the death of her soldier son, Peter, a loss she never got over. She began piece of work on War in 1919, ultimately finding woodcuts as the right medium to give expression to the atrocities she experienced and saw. The finished work is vii woodcuts of unadulterated anguish – in one, a mother offers her baby up as a sacrifice to the cause; in some other, a widow lies in anguish, nearly dead herself. "I have tried again and again to represent state of war. I was never able to capture information technology… These prints should be sent all over the world and requite everybody the essence of what it was like," Kollwitz wrote in a letter to Romain Rolland in 1922.

Banksy'due south 2016 creation drew attending to the refugee crunch (Credit: Alamy)

There's perhaps no better nowadays-24-hour interval example of an artist giving bureau to a viewer than graffiti artist Banksy's 2016 "Les Mis" image, part of a serial of works criticising the utilize of teargas in the refugee camp in Calais, France. The graffiti – featuring Cosette, the immature heroine of the pic and musical Les Misérables, with tears in her optics from CS gas used to clear refugee camps – appeared overnight opposite the French Embassy in London. The artwork was interactive. Under the image was stencilled QR code that could link viewers to an online clip of a police raid on the camp.

Ii other Banksy works on the theme appeared, including in Calais. They were critically well received (and even embraced) by political authorities, including the mayor of Calais – who was not known for her leniency towards migrants or those wanting to help them. Mayhap in the same manner equally Franco in Espana, she was responding to the prestige, and tourist potential, of having her boondocks "Bansky'd"; she promised to preserve the graffiti under glass while vowing to cover up or erase works past lesser-known graffiti artists. She even made it role of guided tours of the metropolis. (Merely as with political movements, political fine art has the potential to be hijacked.)

The question "What is art?" is certainly not just a question of aesthetics and technique. Past giving grade to outrage, art finds another purpose. Simply it has still another: ane of healing. As Ettinger said in the New York Times discussion: "When violence kills trust, fine art is the infinite where a trust in the other, and past extension of ane's being in the world, can re-emerge."

If you would like to annotate on this story or annihilation else you have seen on BBC Culture, caput over to our Facebook page or bulletin us on Twitter .

And if you liked this story, sign upwardly for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Civilization, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20210706-kent-monkmans-the-scream-images-that-define-atrocities

0 Response to "The Scream Is Part of Which Style in Art"

ارسال یک نظر